Good product positioning spurs buyers to act and empowers revenue teams to win, retain and grow customers. Here’s how.

- Gartner client? Log in for personalized search results.

Tech Product Positioning Done Right

Compelling product positioning also needs a persuasive message

Product positioning must capture the value proposition in a way that motivates both buyers and sellers. But even great product positioning can falter without good messaging.

Download these quick tips on writing persuasive messaging, including:

Knowing the audience and their needs

Proving the worth of your product

Focusing on differentiating value

Articulating that value in impactful storytelling

Product positioning isn’t just for marketing; it’s the key to strategy

Tech products are increasingly difficult to differentiate. Use a framework to populate key elements of your product positioning and tell a value story that really resonates with would-be buyers.

Product Positioning 101

Product Differentiation

Tech-Product Storytelling

Product Authenticity

Five common mistakes in tech product positioning

Product positioning is meant to capture and clearly articulate the differentiated value proposition of a product in a way that motivates buyers to act and empowers revenue teams to win, retain and grow customers. In other words, product positioning is the internal statement of strategy.

Tech products (tangible products, services or solutions delivered as a service) require a detailed level of positioning, particularly when it comes to customer needs, so while product positioning is a well-understood aspect of go-to-market activities, many tech marketers still struggle to develop an easy-to-understand, detailed and differentiated story for their products and solutions.

Too often, for example, target prospect profiles are loosely defined, making it appear as if the vendor’s solution applies to anyone, anywhere. Or tech marketers focus only on the technology and not the business problem it solves — when the solution is what’s most critical to the target buyer.

These are among the most common product positioning failures:

No link between the buyer’s needs and key benefits or most compelling reason to buy. The “who” is the buying entity that needs your product or solution, which should connect to the “that” statement that demonstrates resolution. And the “that” statement should omit benefits not directly related to the customer’s business challenge or needs.

Lack of insight into the target customer or buying team at an enterprise level. Organizations often buy B2B technology products and services through a buying committee made up of members from IT, security, legal, finance and lines of business. Product positioning should speak to enterprise business needs, not the individual people being sold to.

Poor understanding of the competitive landscape. The “unlike” statement is a way to highlight how a technology product or service is different from others in the market. To develop such a statement, you need deep knowledge of the market segment’s competitive offerings.

Weak alignment to target markets and vertical industries. Serving disparate target markets and verticals usually means positioning for each target market serviced vs. using one catch-all statement for multiple markets.

Absence of relatable product/service category and/or the belief that a new category is being created. Category is a positioning anchor. It shapes how your ideal buyer will relate to and perceive your offer and differentiation. Anchor with a category your buyer knows.

Done right, your product positioning will yield a clear statement that includes:

A definition of the buyer

Business needs and wants

Product/service name

Product/service category

Compelling reason to buy

Differentiation

Importantly, the positioning framework and statement are not just marketing tools; they provide the context that everyone in the company needs to be able to apply and tell the story of the business in a consistent manner.

Finding points of differentiation is especially challenging in tech products

Technology products are easily copied and many markets are very mature so features become very similar and make it hard to differentiate the choice for buyers.

Forward-thinking companies therefore look beyond product features for differentiation and the best starting point is usually market segmentation. Take time to focus on customers that are best suited to you because of their needs, desires and fit. This helps you to refine your product positioning to differentiate yourself within that segment.

Once you have refined your segmentation, you can explore differentiation options by considering a number of dimensions, including:

Clarifying the competition (including the status quo, which may include nontechnical approaches)

Customer experience (like customer service, onboarding process or other emotional factors)

Market stage (newer markets versus more mature, commoditized segments)

As you work to define differentiation, remember its true meaning: Differentiation is how you are different from something else. Long lists of differentiators without context don’t work as buyers simply ignore or refute them.

Validate your differentiators

Keep in mind that buyers’ priorities and expectations also change — sometimes in response to internal changes, competitive pressures or macroeconomic dynamics. Whatever the reason, they rarely stay the same over time, especially in the tech landscape.

Innovation was once the primary competitive differentiator for technology — with innovative products offering better ways to capture value and new vendors constantly “one-upping” existing players. Today, the cases where product differentiation offers real competitive advantage are rare and short-lived.

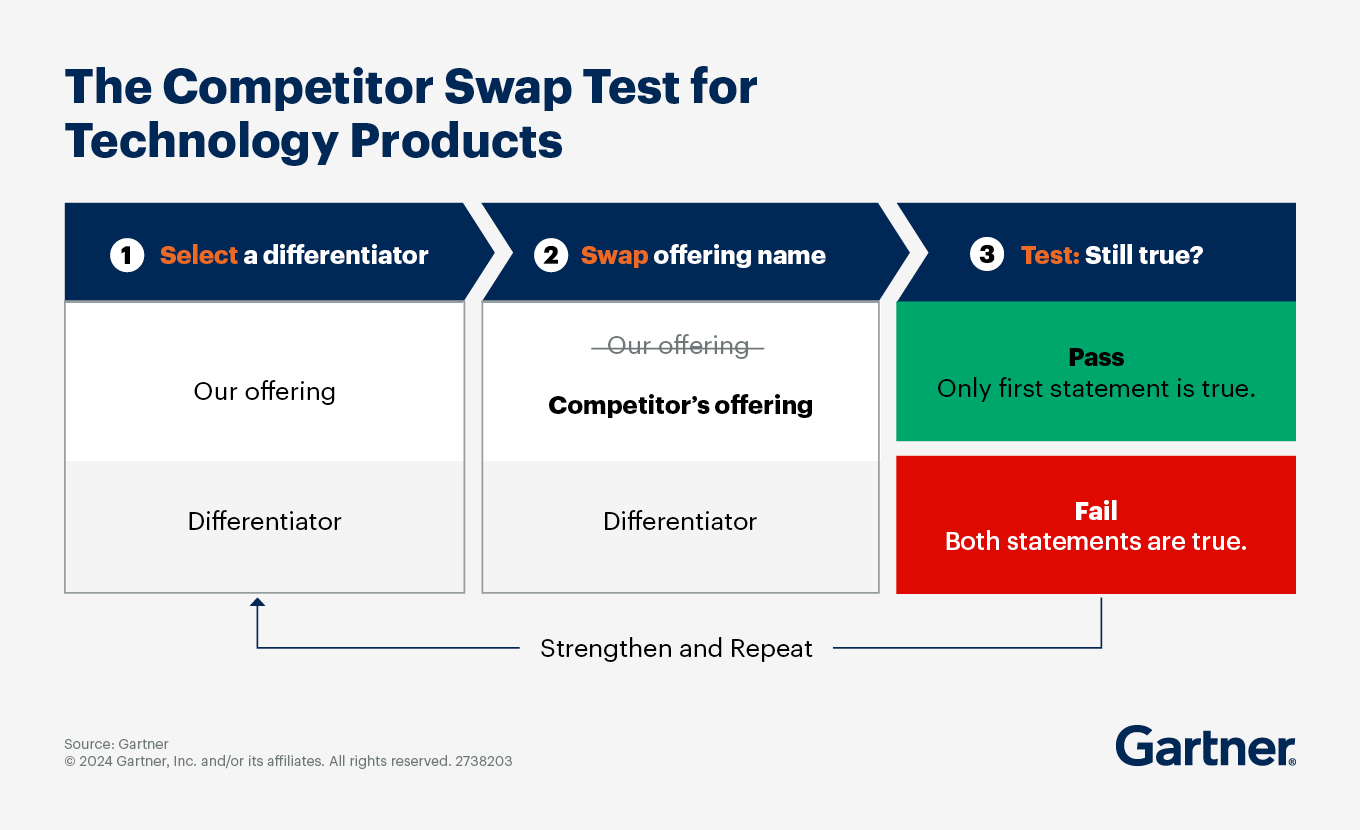

In short, if you are able to innovate to create product differentiation, exploit it aggressively, but be prepared to be copied. And revisit key competitors and target buyer profiles regularly to ensure you are considering an up-to-date buyer perspective and competitive capabilities and then retest your differentiators using the competitor-swap test:

Select: Identify a differentiator you’d like to test.

Swap: Replace your product or company with the name of a competitor.

Test: Pressure-test the differentiation claim. Determine if the statement is still true (whether it could be credibly claimed by the competitor). If not, your differentiator is strong enough. If the new statement rings true, your differentiator is not valid for your offering.

Use storytelling to help tech buyers to understand product value

Marketing messages are often ineffective in connecting with tech buyers. Typical shortcomings include:

Failing to provide context so customers don’t see how they fit within the story in terms of their situation, problems and opportunities.

Relying too heavily on features and specifications, rather than citing customer examples and creating emotional connections — which can lead to customer mistrust and delayed purchases.

Attempting to deliver all aspects of a go-to-market message at once, overwhelming buyers and leading them to disengage from buying journeys.

Use storytelling techniques, driven by your positioning statement, to help you connect customer situations to product/service capabilities and outcomes. Align those storylines to the questions that buyers need answered, taking into account specific audience requirements.

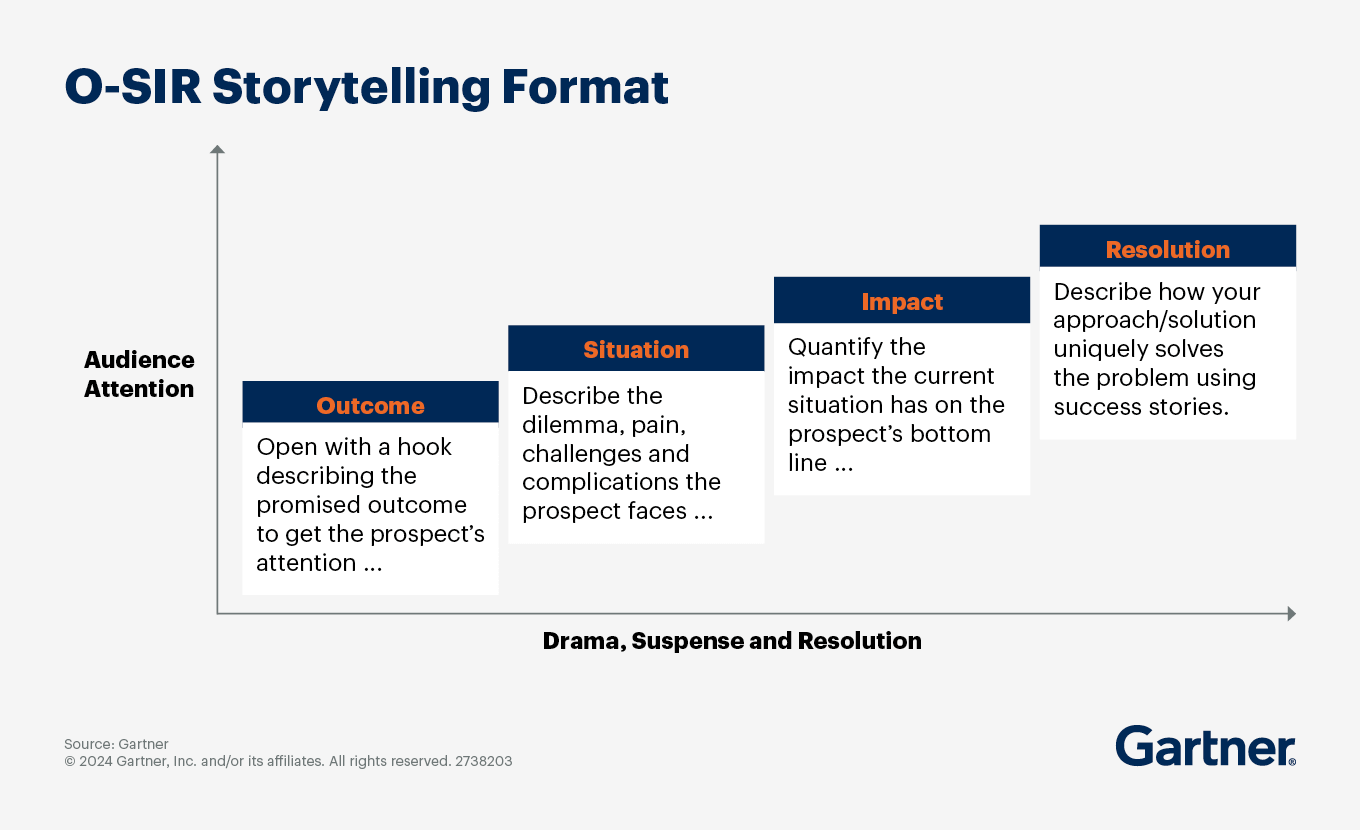

Storytelling is more than just crafting catchy messaging. Devise them rigorously, using the Gartner recommended model: outcome, situation, impact and resolution:

Outcome — Lead with the business or experiential benefits that can be obtained by the client. While this seems backward, buyers are inherently self-interested and are looking for clear and concise descriptions of what you will be able to do for them. Tie these outcomes to real-world data when possible to drive reader interest and to ground the results in reality.

Situation — Failure setting up a case study usually means a lack of clarity about the client being helped, the nature of the problem they experienced or a lack of focus on the client altogether. This first section of the narrative should introduce the main characters, including minimal biographical information about the company, as well as the challenges they face. The focus should remain on the client and ideally the vendor should not be mentioned until the next story element.

Impact — Authors often confuse the impact with the situation, and fail to extrapolate the larger business value lost due to the effects of the problems stated. For example, a case study that points to a feature, stating “Company X wanted to migrate to the cloud,” is much less impactful than one that points to a value, with “Company X needed to reduce capex and improve collaboration, and chose to move to the cloud.” In the latter example, the impact of the previously described situation becomes much clearer.

Resolution — A successful resolution, the final element of a narrative, has two distinct parts: the tactical improvements made by the vendor to create change, and what the business outcomes of that change are. The resolution loses clarity when the former is missing, and loses power when the latter is absent. It is essential to cover both the changes made by the organization as well as the positive outcomes. These should also mirror the challenges established in the situation, completing the narrative while leaving no idea planted without a payoff.

Case studies done right add authenticity to the product value story

The "R" segment of a “situation-impact-resolution” story should include customer testimonials/case studies to answer questions like, “What is it like to work with the vendor? What does a successful implementation look like?"

Real-life customer case stories are the surest way to be authentic in your storytelling, but case studies often fall short of their promise to persuade readers through example. For example:

Case studies often either leave out elements essential to the story or confuse a case study with a list of use cases.

Lack of specificity also makes them seem suspect and lack relevance, and trying to use one case study for multiple purposes leaves the take-aways unclear.

Using case studies to define the value proposition rather than reinforce it, causes organizations to lose control of their own narrative.

Case studies often fail to provide the next best action for their audience, wasting the positive impact of a well-told story.

If you want to make authentic stories even more believable, show quantifiable impact. Buyers will more likely believe you if you can attach values to specific situations and outcomes — especially if they are linked to customer examples.

One of the most important benefits of storytelling is that it creates an environment for emotional connections. The human brain uses emotions and previous experiences to remember; they don’t remember lists of features or facts.

To create a good product-value stories:

Craft a complete client-focused narrative, rather than an example scenario, by including all stages: situation, challenge, impact and resolution.

Focus the narrative on supporting one key aspect of the value proposition by being as specific as possible instead of trying to speak to everything at once.

Use the story explored in the case study to support the defined value proposition, rather than having the case study define it.

Guide the reader of the case study to their next best action to move them along the marketing funnel.

Attend a Conference

Join Gartner experts and your peers to accelerate growth

Join CMOs and marketing executives to learn how to navigate emerging trends and challenges. From peer-led sessions to analyst one-on-ones, you'll leave ready to tackle your mission-critical priorities.

Gartner Marketing Symposium/Xpo™

Denver, CO

Drive stronger performance on your mission-critical priorities.